Lent: April 18th

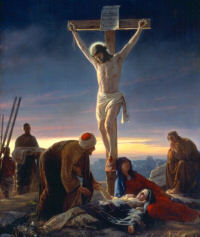

Good Friday of the Lord’s Passion

Other Titles: God's Friday; Great Friday; Holy Friday

» Enjoy our Liturgical Seasons series of e-books!

"It is accomplished; and bowing his head he gave up his spirit."

Today the whole Church mourns the death of our Savior. This is traditionally a day of sadness, spent in fasting and prayer. The title for this day varies in different parts of the world: "Holy Friday" for Latin nations, Slavs and Hungarians call it "Great Friday," in Germany it is "Friday of Mourning," and in Norway, it is "Long Friday." Some view the term "Good Friday" (used in English and Dutch) as a corruption of the term "God's Friday." This is another obligatory day of fasting and abstinence. In Ireland, they practice the "black fast," which is to consume nothing but black tea and water.

Liturgy

According to the Church's ancient tradition, the sacraments are not celebrated on Good Friday nor Holy Saturday. "Celebration of the Lord's Passion," traditionally known as the "Mass of the Presanctified," (although it is not a mass) is usually celebrated around three o'clock in the afternoon, or later, depending on the needs of the parish.

According to the Church's ancient tradition, the sacraments are not celebrated on Good Friday nor Holy Saturday. "Celebration of the Lord's Passion," traditionally known as the "Mass of the Presanctified," (although it is not a mass) is usually celebrated around three o'clock in the afternoon, or later, depending on the needs of the parish.

The altar is completely bare, with no cloths, candles nor cross. The service is divided into three parts: Liturgy of the Word, Veneration of the Cross and Holy Communion. The priest and deacons wear red or black vestments. The liturgy starts with the priests and deacons going to the altar in silence and prostrating themselves for a few moments in silent prayer, then an introductory prayer is prayed.

In part one, the Liturgy of the Word, we hear the most famous of the Suffering Servant passages from Isaiah (52:13-53:12), a pre-figurement of Christ on Good Friday. Psalm 30 is the Responsorial Psalm "Father, I put my life in your hands." The Second Reading, or Epistle, is from the letter to the Hebrews, 4:14-16; 5:7-9. The Gospel Reading is the Passion of St. John.

The General Intercessions conclude the Liturgy of the Word. The ten intercessions cover these areas:

- For the Church

- For the Pope

- For the clergy and laity of the Church

- For those preparing for baptism

- For the unity of Christians

- For the Jewish people

- For those who do not believe in Christ

- For those who do not believe in God

- For all in public office

- For those in special need

For more information about these intercessions please see Prayers for the Prisoners from the Catholic Culture Library.

Part two is the Veneration of the Cross. A cross, either veiled or unveiled, is processed through the Church, and then venerated by the congregation. We joyfully venerate and kiss the wooden cross "on which hung the Savior of the world." During this time the "Reproaches" are usually sung or recited.

Part three, Holy Communion, concludes the Celebration of the Lord's Passion. The altar is covered with a cloth and the ciboriums containing the Blessed Sacrament are brought to the altar from the place of reposition. The Our Father and the Ecce Agnus Dei ("This is the Lamb of God") are recited. The congregation receives Holy Communion, there is a "Prayer After Communion," and then a "Prayer Over the People," and everyone departs in silence.

Activities

This is a day of mourning. We should try to find ways to slow down and have more quiet to contemplate this solemn day. Many people take time off from work and school to participate in the devotions and liturgy of the day as much as possible. Some families leave house dark and maintain some silence during the 3 hours (noon — 3p.m.), and keep from loud conversation or activities throughout the remainder of the day. Other ideas for keeping the day solemn is restricting ourselves from any outside entertainment—TV, music, computer, phones, social media, games—these are all types of technology that can distract us from the spirit of the day.

This is a day of mourning. We should try to find ways to slow down and have more quiet to contemplate this solemn day. Many people take time off from work and school to participate in the devotions and liturgy of the day as much as possible. Some families leave house dark and maintain some silence during the 3 hours (noon — 3p.m.), and keep from loud conversation or activities throughout the remainder of the day. Other ideas for keeping the day solemn is restricting ourselves from any outside entertainment—TV, music, computer, phones, social media, games—these are all types of technology that can distract us from the spirit of the day.

If some members of the family cannot attend all the services, a little home altar can be set up, by draping a black or purple cloth over a small table or dresser and placing a crucifix and candles on it. The family then can gather during the three hours, praying different devotions like the rosary, Stations of the Cross, the Divine Mercy devotions, and meditative reading and prayers on the passion of Christ.

Although throughout Lent we have tried to mortify ourselves, it is appropriate to try some practicing extra mortifications today. These can be very simple, such as eating less at the small meals of fasting, or eating standing up. Some people just eat bread and soup, or just bread and water while standing at the table.

For a more complete understanding of what Our Lord suffered read this article On the Physical Death of Jesus Christ (JAMA article) taken from The Journal of the American Medical Association.

Meditation for Good Friday

The liturgies of the Paschal Triduum are one continuous act of worship. There was no dismissal from the Evening Mass of the Lord's Supper last night. There is no formal beginning of today's Celebration of the Lord's Passion, nor is there a dismissal at its end. Tomorrow, the Easter Vigil of Easter will simply begin, with the Service of Light. It is all one action, this commemoration of the axial point of human history and the beginning of the end time—the time of fulfillment.

Today, at the midpoint of the Triduum, the Lenten pilgrimage comes at last to Calvary, where the Church ponders the judicial murder of Jesus of Nazareth, whose obedience to the will of the Father, even to the last extremity of a cruel and degrading death, reveals him to be, in truth, the Son of God. Pope Benedict XVI's reflections on the royal dimension of Good Friday—in which the Cross becomes the coronation throne of the Messiah acclaimed by the crowds on Palm Sunday—serve as an apt introduction to the liturgical texts of the day:

Christ's execution notice became with paradoxical unity the "confession of faith," the real starting-point and rooting-point of the Christian faith, which holds Jesus to be the Christ: as the crucified criminal this Jesus is the Christ, the King. His crucifixion is his coronation; his coronation or kingship is his surrender of himself to men, the identification of word, mission, and existence in the yielding up of this very existence. His existence is thus his word. From the Cross faith understands in increasing measure that this Jesus did not do and say something; that in him person and message are identical, that he always already is what he says.

The first reading at today's commemoration of the Passion is the fourth and greatest of Isaiah's Suffering Servant songs. Read through the eyes of Christian faith, the fourth song becomes the Church's reflection at the foot of the Cross, where two millennia of believers have stood beside Mary, John, and the holy women. Isaiah's harsh descriptions of the Servant —"His appearance was so marred, beyond human semblance, ... he had no form or comelinesss that we should look at him,... he was despised and rejected by men, ... and we esteemed him not" —is all the more striking for its following hard upon a comforting vision of messianic expectation: "How beautiful upon the mountains are the feet of him who brings good tidings, and who publishes peace, who brings good tidings of good, who publishes salvation... for the LORD has comforted his people, he has redeemed Jerusalem" [Isaiah 52:7]. At the foot of the Cross, the Church wonders how it could have come to this: how did the messianic fervor of Palm Sunday yield, in less than a week, the condemnation and brutalization of the promised deliverer? The answer of faith is given at the end of the fourth Servant song: death is not the Servant's final destination, for the Just One "shall make many to be accounted righteous," for he will have borne "their iniquities" while making "intercession for the transgressors."

While meditating upon this divinely ordained destiny of the Suffering Servant, the Church prays, with her crucified Lord, a confession of trust in God through Psalm 31. Then the author of the Letter to the Hebrews reflects on the radical, history-changing redemption won by Jesus: the Suffering Servant who has become the High Priest of the New Covenant, sealed in his blood, is the mediator through whom we can "with confidence draw near to the throne of grace, that we may receive mercy." The Letter to the Hebrews is an extended meditation on the unity of God's salvific purposes in calling Israel to be his chosen people and in sending his Son as Redeemer of the world; today's reading falls squarely within that unity of Old and New Testaments. The Exodus of Israel from Egypt, begun with the Passover meal, was a deliverance from political bondage into freedom and nationhood, and the paradigmatic sign of an even greater liberation to come. In the Passover of the New Covenant, Jesus, passing over from death to resurrected life, offers humanity an eternal and definitive liberation—freedom from sin and its consequence, death; freedom for life within the light and love of the Trinity; freedom lived now within the fellowship of the People of God, composed of both Jews and Gentiles; freedom lived for all eternity in the communion of saints, at the Wedding Feast of the Lamb.

The Johannine Passion narrative read today displays in its most dramatic form a key feature of the fourth gospel with which Lenten pilgrims have become familiar over the past two and a half weeks: Jesus's sovereign command of his destiny. The Passion is emphatically not something that happens to Jesus. The Passion is the destiny that Jesus embraces. At every moment in today's narrative, it is Jesus who drives the drama forward: in the garden, where he is arrested; at his interrogation by the Temple aristocracy; in the quasi-judicial proceeding before Pilate; in addressing Mary and John from the Cross; in declaring his mission finished and giving over his spirit.

Jesus's testimony to truth before Pilate is particularly striking in the cultural circumstances of the early twenty-first century, in which, for many, the only secure truth is that there is no such thing as the truth, only partial and personal truths. Pilate can stand for those with an insecure grasp upon the truth today: What, he asks, is truth? The only "truth" that counts here is that I, Pilate, have absolute power over you, Jesus. Not so, Jesus replies. I have told the truth about myself and my mission; the truth is that this mission poses no threat to you; and yet for reasons of expedience you are prepared to condemn me—a condemnation that would not be possible unless this were, in ways you cannot understand, part of the divine plan. You ask, thinking it an argument-stopper, "What is truth?" I answer: This is the truth, it is embodied in me, and I spoke it at the very beginning of my public ministry— "God so loved the world that he gave his only Son, that whoever believes in him should not perish but have eternal life" [John 3.16]. And all of this is of the will of God, who is Truth: "You would have no power over me unless it had been given you from above...."

John's account of the crucifixion is deeply ecclesiological, arising as it does from the faith and experience of the Church. For John, reflecting the way in which the first Christian generations understood the drama of Calvary, the Church is born at Calvary. From the earliest days of Christian faith, the water and blood that issued from the pierced side of Christ were understood to be signs of Baptism and the Eucharist, the sacrament from which Christians are born and the sacrament by which Christians are fed. The Fathers of the Church in the first Christian centuries understood the "tunic... without seam" that is stripped from Jesus before his crucifixion—the seamless garment that cannot be torn—as a sign of the indestructible unity of the Church. That unity is also embodied in the dramatis personae of the Johannine Passion narrative: Mary, John, the holy women; Peter in his denial; those who are not present at Calvary, including the disciples who are cowering somewhere in fear or shame or both; Joseph of Arimathea and Nicodemus, who arrive on the scene late; the centurion moved to faith, who is the beginning of the Gentile Church. All of these figures are uniquely touched by the divine mercy radiating from the Cross; all of them, whatever their behavior on Good Friday, are united in the Church.

Station church pilgrims may also see themselves in this drama, for, as Pope Benedict XVI pointed out in Jesus of Nazareth—Holy Week, the soldiers at the Cross are not the only ones who offer the dying Jesus sour wine or vinegar: "It is we ourselves who repeatedly respond to God's bountiful love" —that "thirst" of which Jesus spoke to the Samaritan woman weeks ago— "with a sour heart that is unable to perceive God's love. 'I thirst': this cry of Jesus is addressed to every single one of us."

As Pope Benedict's interpretation reminds us, the Passion according to St. John invites us to "see" what is happening today against a transcendent and salvific horizon, not simply a historical horizon. These things happened; but they are pregnant with meaning, and the interplay of event and meaning is the key to grasping that this is indeed the axial moment, the turning point of human history. Moreover, this "moment" is so rich in meaning that it will continue to resonate throughout history. Today's station, the Basilica of the Holy Cross in Jerusalem, houses many of the relics of the Passion that Helena, mother of Constantine, brought from Jerusalem to Rome in the early fourth century. The basilica is in the midst of a busy Roman neighborhood where, Christians believe, the work begun on Calvary (of which the relics of the Passion are the tangible, physical evidence) continues—as it continues around the world.

—George Weigel, Roman Pilgrimage: The Station Churches

Good Friday of the Lord's Passion

Station with Santa Croce in Gerusalemme (Holy Cross in Jerusalem):

The Station today returns to the church of the Holy Cross in Jerusalem which contains parts of the true Cross and one of the nails of the Crucifixion. The Church commemorates the redemption of the world with the reading of the Passion, the Collects in which the Church prays with confidence for the salvation of all men, the veneration of the Cross and the reception of Our Lord reserved in the Blessed Sacrament.For more on Santa Croce in Gerusalemme, see:

For further information on the Station Churches, see The Stational Church.